What It Means to Die for What You Believe

When Faith Becomes More Valuable Than Life Itself

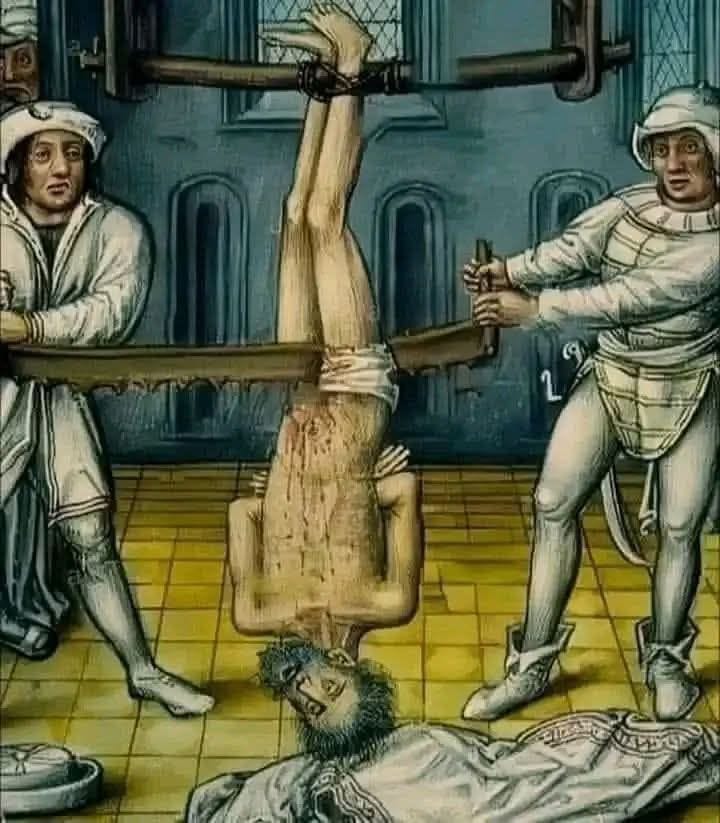

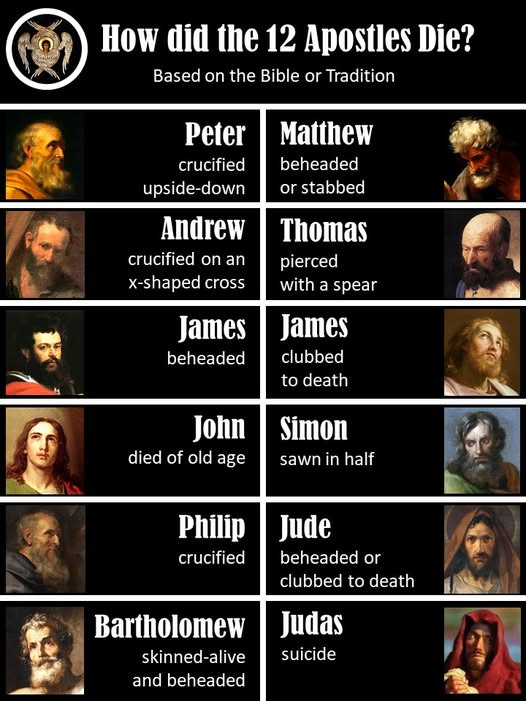

There’s a question that separates people who talk about their beliefs from people who actually have them: what would you die for? Not what cause would you support, not what principle sounds noble at a dinner party, not what position you’d argue for online. What truth have you encountered so completely that you’d choose torture over betraying it? Most of us will never answer that question because we’ve spent our lives avoiding it, arranging our comfortable existence so we’re never forced to choose between our convictions and our survival. But some people have answered it. The apostles of Christ answered it when they were boiled in oil, flayed alive, crucified upside down, and dragged through streets by horses until they died. They answered it not because they were religious fanatics divorced from reality, but because they had seen something so real that denying it became impossible even when denial meant living. And whether you’re a Christian reading this for encouragement or a secular person fighting against corruption, injustice, or evil in a world that punishes truth-tellers, their example matters for the same reason: real power protects itself violently, and if you’re going to stand against it, you need to understand what it looks like when belief becomes stronger than the fear of death.

Because that’s the only thing that’s ever actually changed anything.

You don’t have to be a Christian to understand what happened when the apostle Andrew, bound to an X-shaped cross with cords instead of nails to prolong his suffering, looked at the instrument of his execution and said “I have long desired and expected this happy hour.” You don’t need to believe in God to recognize something extraordinary in a man who preached to his torturers for two days while dying. You don’t need to share someone’s faith to understand that what you’re witnessing is the difference between people who believe things and people who believe things so deeply that nothing, not torture, not death, not the promise of freedom if they’d just shut up and recant, could make them stop.

The early followers of Christ died in ways that make modern persecution look like a parking ticket. Matthew was killed by sword in Ethiopia. Mark was dragged by horses through the streets of Alexandria until his body gave out. Luke was hanged in Greece. Peter was crucified upside down because he told his executioners he wasn’t worthy to die the same way Jesus had. James, the leader of the church in Jerusalem, was thrown a hundred feet from the pinnacle of the Temple, and when he survived the fall, they beat him to death with a club. Bartholomew was flayed alive with whips. Thomas was stabbed with a spear in India. Jude was killed with arrows. Paul was beheaded by Nero after years of imprisonment.

John, perhaps the most remarkable of all, was boiled in a basin of oil and didn’t die. They sent him to the prison island of Patmos instead, where he wrote the Book of Revelation, the most apocalyptic and strange text in the entire Bible, a fever dream of judgment and cosmic war that has haunted Western imagination for two thousand years. He was eventually freed and died peacefully as an old man, the only apostle to avoid martyrdom. But he didn’t avoid suffering. He just survived it.

These men didn’t die because they were confused or deluded or caught up in mass hysteria. They died because they refused to stop talking. They died because when given the choice between their lives and their message, they chose the message. Every single time. They could have walked away. They could have said the right words, made the right compromises, kept their heads down, and lived long comfortable lives. They didn’t. And the reason they didn’t should disturb anyone who thinks they believe in anything.

What does it mean to believe something? Not to prefer it, not to think it’s probably true, not to find it comforting or useful, but to actually believe it in a way that governs your behavior when everything is on the line? Most of what we call belief is just opinion with intensity. We believe things until believing them becomes inconvenient, until the cost gets too high, until someone offers us an easier path. Real belief, the kind that these men demonstrated, doesn’t calculate cost. It doesn’t weigh options. It doesn’t negotiate. It simply is, and it remains, and it speaks, even when speaking means dying.

The Roman officer who guarded James the son of Zebedee watched him defend his faith at trial and was so moved by what he saw that he declared himself a Christian on the spot and knelt beside James to be beheaded too. Think about that. This was a man whose job was to kill James. He had no prior commitment to Christianity. He had everything to lose and nothing to gain. He watched another human being face death with such conviction that it broke something open in him, and he chose the same death rather than live without whatever he’d just witnessed. That’s not stupidity. That’s not brainwashing. That’s someone encountering something real enough that his entire framework for understanding the world collapsed and rebuilt itself in minutes.

You don’t have to believe what James believed to recognize that what he had was something most of us don’t have about anything. How many of us believe in our political ideologies strongly enough to die for them? How many of us believe in our moral principles enough to accept torture rather than compromise? How many of us believe in anything at all with that kind of totality? We have preferences, affiliations, identities we’ve chosen because they’re socially advantageous or emotionally satisfying. We have opinions we’re willing to argue about at dinner parties. We have causes we’ll support as long as supporting them doesn’t cost too much. But do we have beliefs? Real ones? The kind you’d die for?

And here’s what should really unsettle you, these men didn’t die for abstract theological propositions. They died for testimony. They died because they claimed to have seen something, to have encountered someone, to have experienced something that changed everything. And when authorities told them to shut up about it, they couldn’t. Not wouldn’t. Couldn’t. The thing they’d encountered was too real, too important, too central to everything that mattered for silence to be possible. They died because they were witnesses, and witnesses talk, and talking got them killed.

The martyrdom of the apostles matters even if you’re not a Christian because it demonstrates something about human beings that our comfortable modern world lets us forget.

We are capable of believing things so completely that death becomes preferable to betrayal. We are capable of encountering truths so overwhelming that no threat can make us deny them. We are capable of conviction that doesn’t bend, doesn’t compromise, doesn’t calculate odds or measure costs. We’re capable of it, but most of us never get there. Most of us never believe anything that deeply. Most of us spend our lives in the shallow end, holding opinions we’d abandon the moment they become expensive.

Modern protest is theatrical. People march with signs, chant slogans, maybe risk arrest if they’re feeling brave. They’ll post on social media, sign petitions, donate money to causes, attend rallies where everyone agrees with them already. This isn’t meaningless, but it’s not what the apostles did. The apostles didn’t protest. They testified. They didn’t demand change. They proclaimed truth. And they kept proclaiming it until it killed them, and even then they kept proclaiming it while dying. Andrew preached from his cross for two days. Two days of dying, of suffocating slowly as his body weight pulled against the cords binding him, of unimaginable pain, and he used that time to talk about Jesus. That’s not protest. That’s something else entirely.

What would that look like now? What would it mean to believe something so completely that you couldn’t be threatened or bribed or tortured into silence? Not because you’re stubborn or prideful or trying to prove something, but because the thing you believe is more real to you than your own survival instinct? Most of us will never know. Most of us have arranged our lives specifically to avoid ever being tested that way. We’ve made compromises so early and so often that we don’t even recognize them as compromises anymore. We’ve learned to believe things conditionally, to hold our convictions loosely, to always leave ourselves an exit.

The early church grew because people watched Christians die and couldn’t explain what they were seeing. These weren’t zealots throwing their lives away for a political cause. These weren’t soldiers dying in battle. These were ordinary people, fishermen and tax collectors and merchants, who encountered something that rewired them completely. And when the empire told them to recant or die, they died. Hundreds of them. Thousands of them. They died in arenas, they died on crosses, they died in prisons, they died in obscurity with no one watching except their executioners. And the church grew anyway because death couldn’t silence testimony. Because people kept watching other people choose death over betrayal and kept asking themselves what could possibly be worth that.

You might think this is about religion, about Christianity specifically, about theological claims you don’t accept. But it’s not. It’s about what it means to encounter truth. Not truth as abstract principle or logical proposition, but truth as lived experience, as something so real and overwhelming that you can’t un-know it, can’t pretend you didn’t see it, can’t go back to who you were before. The apostles died because they saw something. And once you’ve seen certain things, once you’ve encountered certain realities, silence becomes impossible. The cost of speaking might be death, but the cost of silence is worse. The cost of silence is betraying the most real thing you’ve ever known.

This is what separates actual belief from social performance. Actual belief can’t be threatened out of you because it’s not a choice you’re making. It’s a reality you’ve encountered. Social performance evaporates the moment it becomes dangerous. Actual belief only becomes more visible under pressure. You can tell what someone really believes by watching what they do when everything is on the line. You can tell what you really believe the same way.

How many of us have ever been tested? How many of us have faced a moment where our stated beliefs would cost us everything if we held to them? How many of us have arranged our lives specifically to avoid such moments? We sign petitions online. We share articles. We vote. We argue with strangers on the internet. We feel very strongly about things. And none of it costs us anything real. None of it requires us to choose between our comfort and our convictions. None of it puts us in a position where we have to decide if what we claim to believe is worth dying for.

The apostles didn’t die building megachurches or accumulating wealth or achieving political power. They died winning souls, which is to say they died talking to people about what they’d seen and experienced, one conversation at a time, knowing that each conversation might be the one that got them killed. They died as witnesses, which is the original meaning of the word martyr. They testified until testimony became fatal. And the reason their deaths matter, even to people who don’t share their faith, is because they demonstrate what human beings are capable of when we encounter something real enough that survival becomes secondary.

Most of what passes for belief in modern life is just tribalism with a vocabulary. We believe what our tribe believes because believing it signals membership. We hold the right opinions, support the right causes, oppose the right enemies. And we’ll keep holding those opinions right up until holding them becomes genuinely costly, at which point we’ll discover we didn’t really believe them at all. We were just participating in a social game. The apostles weren’t playing a game. They were testifying to something they’d seen, and they kept testifying even when testimony meant torture and death.

You don’t have to be a Christian to recognize that this kind of conviction is rare and valuable and mostly absent from contemporary life. You don’t have to believe in the resurrection to understand that men who die horrible deaths rather than recant their testimony probably saw something. You don’t have to accept their theological framework to recognize that what they had, whatever you want to call it, is something most of us lack. They had encountered reality in a way that made everything else negotiable except the truth of what they’d encountered. They had seen something that made death preferable to betrayal.

So what have you seen? What have you encountered that you couldn’t be threatened into denying? What truth has grabbed you so completely that silence would be worse than death? Or have you spent your whole life in the safe middle distance, holding opinions that cost nothing, supporting causes that require no sacrifice, believing things that never get tested because you’ve arranged your life to avoid the test?

The apostles died without building big churches. They died without accumulating wealth. They died without political power or social prestige or the admiration of respectable society. They died as criminals and troublemakers and threats to public order. And two thousand years later, we’re still talking about them. Not because they were successful by any conventional metric, but because they were faithful. Because they saw something real and they testified to it and they kept testifying until testimony killed them. Because they believed something that couldn’t be tortured out of them, couldn’t be bribed away, couldn’t be threatened into silence.

That’s what real protest looks like. That’s what real belief looks like. Not performance. Not tribalism. Not opinions held loosely and abandoned when convenient. Real belief means you’ve encountered something so true that betraying it would mean betraying yourself, would mean pretending you didn’t see what you saw, would mean living a lie so fundamental that death becomes preferable. Most of us will never be tested that way. Most of us will die having believed nothing that deeply. Most of us will discover, if we’re honest, that we never really believed much of anything at all.

But some people do. Some people encounter something real enough that everything else becomes negotiable. And when those people speak, when they testify, when they refuse to shut up even as the cost keeps rising, pay attention. Because you’re not watching someone perform belief. You’re watching someone who has seen something that makes performance irrelevant. You’re watching someone for whom truth has become more valuable than life.

Whether you believe what they believe is almost beside the point. The point is that they believe it. Really believe it. The kind of belief that doesn’t bend, doesn’t calculate, doesn’t compromise. The kind of belief that faces death and keeps talking. The kind of belief that most of us will spend our entire lives never knowing.

And maybe that should disturb us more than it does.

A Note from The Wise Wolf & Lily

Thank you for reading. This isn’t the kind of article that makes you feel good or gives you easy answers, but it’s the kind of journalism we believe matters.

The Wise Wolf doesn’t take corporate money. We don’t run ads. We don’t soften our coverage to please billionaires or political parties. We’re entirely reader-supported, which means I’m paying my way through journalism school by doing this work instead of drowning in student loans or compromising my integrity for some corporate outlet that would never let us publish articles like this.

If this article made you think or challenged you, consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you can’t afford that right now, share this piece instead. The algorithm buries content like this because it threatens comfortable assumptions. We need you to be the algorithm.

Every share is an act of resistance. Every subscription keeps independent journalism alive and keeps me in school doing work that matters. The people who profit from your comfortable lies have billions of dollars. We have you.

Thank you for being here. Thank you for reading something that asks hard questions.

“No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country.” Gen. George S. Patton

“We fought the wrong enemy [in WW2]” also Patton

I have often prayed that I have strength when persecution comes.... I know that my faith is real, but my character is veneer thin.

I look to the men and women, the early Christians and I know that I am not of the same mold... I wish I were.....

I don't want to spend my time in shame, I think that stems from pride...

I think what I need to focus on and this is coming to me as I write, that I cannot and am nothing without Jesus...